How much moisture does a new building release and do I need to worry about it?

Depending on where, when, how fast, and how well you build, construction moisture—sometimes called “built-in” moisture—may require significant one-time management.

I learned from my grandmother that my great-grandfather was a Pennsylvania home builder. She told us that he never built a home in the winter; she played in his woodshop much of the winter as he built cabinets, doors, windows, stair parts, and trim for the home or homes he would build when the weather permitted in the spring.

This would have been about the turn of the 20th century.

I bet he built homes slowly, never closing in a home until about six months after the foundation was cast. His homes probably leaked air like a sieve, were uninsulated, and were heated with wood—a lot of it. I doubt he gave even a passing thought to all the moisture released in the first year of the building’s life.

Fast forward, 100 years or so

Around January 2019, I got a call to look at a home in climate zone 4A—actually it was almost in climate zone 5A—with significant moisture issues. It turns out the home was built in 11 weeks, from breaking ground to occupancy, just in time for Thanksgiving.

While there were bulk water management issues in specific locations, there was also fairly widely distributed mold growth on the interior surface of the plywood sheathing (at least in the walls).

The walls were insulated fairly well with asphalt-impregnated paper-faced fiberglass batts. A blower-door test had been done on the home. The result was 2.8 ACH50, so not Passive House tight, but not a sieve either (the average new home in the U.S. has an airtightness of about 5 to 7 ACH50).

The information above got me thinking about two moisture sources that could significantly raise interior air moisture content: household sources of moisture and construction moisture.

Conducting a one-time building assessment, all I could conclude about household moisture management for this home was that it seemed pretty good: the home had decent spot exhaust fans with good draw and the occupants reported consistent use. There were not that many house plants, no firewood was stored indoors, and it was a pretty big conditioned space for a family of four.

It was the rapid construction schedule that raised a red flag (for just about everybody except the builder, it seemed). And I had a general number in my head for this source of moisture—10 pints or about 10 lb. of water release per day. But rather than an average rate, what about the difference between the first six months vs. later on? And what about this particular house and its size and materials?

Jeff Christian’s Chapter in “Moisture in Buildings”

Moisture in Buildings, edited by Heinz Trechsel, is the seminal resource on the topic named in the book’s title, and the chapter “Moisture Sources,” written by Jeff Christian, is the seminal resource on construction moisture. Here are some statistics for an average house, according to the book:

- About 423 pints (about the same in pounds) of water can be released as the lumber dries to average conditions.

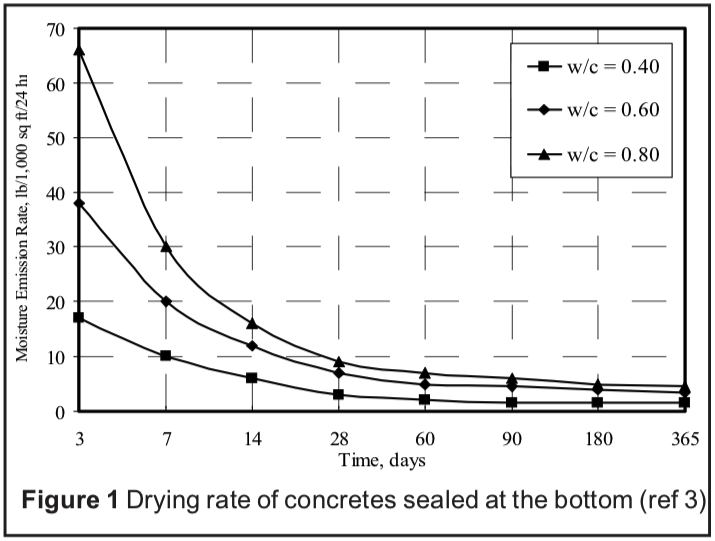

- Basement walls (8.2 ft. high, 10 in. thick, 115 ft. long for a total 29 cu. yd. of concrete) plus the basement slab (I estimate about 1000 sq. ft. and 4 in. thick) at 5.2 cu. yd., gives off 4945 pints (pounds) with most of this moisture released in the first year.

- In the first year new homes can release output an average of 21 pints of water per winter day, all from construction-related sources.

And, some other things to consider:

- If the home’s heating system was not operational during joint-compound work on the drywall, and propane or kerosene heaters were used, that’s about an additional 1 gal. of water (about 8 lb.) for every gallon of kerosene burned. For propane, you can add about a gallon for every therm (90,0000 Btus).

- For every gallon of water-based interior paint, about 4 lb. of water evaporates into the interior.

- The home I inspected had a basement finished with a parge coat on the concrete foundation walls. I’m not sure how much water this would add to the interior, but let’s guess the same as painting the basement walls, at least.

- At some point either just before occupancy or maybe even after, a concrete wet saw was used to cut an egress opening in the basement foundation wall. While some portion of the water was mopped up, we do know that a significant portion of this water evaporated into the building.

Let’s cut to the chase: You can expect thousands of pounds of water to be released to the interior of your new buildings in the first 6 months. Some materials will be releasing lots of water as vapor while others may be picking up or transmitting that water as vapor to deeper components in assemblies. The rate of this vapor emission is not linear for most materials but the moisture load can accumulate if there is no vapor management in the new building.

How much is “a lot of” water?

I have a spreadsheet that I use to calculate how much water it takes to move a certain volume of air from 30% to 80% relative humidity (at 68°F). For the home in question, which is about 4000 sq. ft. with a volume of 36,000 cu. ft., it would take the addition of about 20 lb. of water, and only about a dozen pounds of water to move the air in this house from 30% to 60% interior relative humidity.

I can’t prove that construction moisture was driving the mold growth on the interior of the plywood sheathing, but I am betting that the vapor in the home was great enough during early winter to overwhelm the paper-facing vapor retarder on the batt insulation and result in condensation in the wall cavities.

What can we do about construction moisture?

Here are some circumstances that increase the likelihood of excess construction moisture:

- Concrete in the building

- Good air-sealing work

- Accelerated construction schedule

- Cold-weather construction

- Hot/humid weather construction

The bottom line is that you need to measure and manage construction moisture. Your construction cycle time, your climate, the materials you use, the time of year you close up, the building’s airtightness, and how you heat an under-construction home while protecting the central heating system all can contribute to construction moisture and how actively you need to manage it just as you would if the home were occupied.

Matt Reisinger Build in Austin, Texas

Summer 2019, Steve Baczek and I got to spend the better part of a day touring several of Matt Risinger’s projects. We talked about construction moisture and Matt said, “We have our own mobile dehumidification system set up on a flatbed trailer that we use to dry out our buildings whenever conditions dictate.”

Matt also routinely uses a pin-type moisture meter to assess the moisture content of his materials in addition to monitoring the air inside his under-construction homes.

Do you have a method for managing construction moisture? If so, we’d love to hear about it. Use the comment section below…