Taking a look at only the first three images in the photo gallery for this blog, can you guess what the contraption is (was) in the middle of the basement floor?

OK, now look at Image #3.

Yup, this home — built right next to Baker Brook in Williamsville, Vermont — is a former lumber mill. The contraption in the center of the basement is the remnants of the mill’s water wheel, and in the background you can see a sort of concrete vertical slot or shaft that was the sluiceway.

Building a mill that intentionally connects water flow to the lowest level of the building is a great idea. Not so great for a residence, though.

Hurricane Irene visits Vermont

I first visited this home in the aftermath of Hurricane Irene, which provided a 9-inch soaking on top of already saturated land in 2011. Brooks became rivers during and just after Irene. And for this former mill, Irene reconnected Baker Brook to the basement. The homeowner’s insurance policy covered cleanup and mold mitigation in the home, including severe mold in the vented attic.

I got the call because months later, the mold came back, particularly in the attic. This occurred after the insurance company dropped the homeowner’s coverage. It was no surprise that the mold was back in the vented attic, since the basement was still wet.

I don’t have any real records from this first visit; it was a pro bono project. I do remember advising the homeowner as follows:

- Decouple the brook from the basement. This was just as much about negotiations with local and state government as it was about work under the control of the homeowners. Plenty of Vermonters with land abutting streams and rivers had to work out just what to do — and not do — to address the completely new water flow patterns that Irene created. It took a while, but with what the homeowner felt was mixed results, the basement is no longer part of the brook. See Image #4 to see the results of the embankment work.

- Direct the building’s bulk water load off and away from the structure. They did not want to use gutters, so my recommendation was for an underground roof. (See GBA resources on underground roofs.)

- Dehumidify the basement, in the hopes that this will manage the remaining moisture load evaporating up through the basement slab. At the time, I was aware of floor coatings that claimed to accomplish negative side waterproofing, but I had not yet done the research described in this GBA blog on negative side waterproofing.

- Air seal the attic. The primary source of the attic moisture was, and remains, the basement.

The recommendations were implemented

Fast forward to late fall 2018. The homeowner did install an underground roof; managed to direct most of the surface water away from the home; installed a dehumidifier in the basement; and approached a local and reputable insulation contractor to air seal and insulate the attic. The trouble is, when the insulator went to look at the attic, there was new mold (see Image #5 in the gallery). The insulator said, “No way will we insulate until you get Peter back to reassess the hygrothermal performance of the whole house.”

Here is the rub:

- The older 1-story part of the home (Image #6) is vented exactly the same way as the main 2-story part of the home, but there is no mold anywhere in the older part.

- A significant difference between the two attics is that one is sheathed in plywood, the other with boards.

- I have no way of knowing when the mold came back.

- This mold has a completely different pattern than the first time around.

Here is my theory:

We had an unusually wet and overcast spell of weather in late August, September, and early October 2018 in southern Vermont. For long periods of time, the difference between the air and dewpoint temperature was just a couple of degrees Fahrenheit. I got a rash of calls from folks complaining of all kinds of biological growth in attics and on claddings, particularly facing north (where night sky radiation cooling isn’t countered by solar heating). Surfaces that readily absorbed condensation (like roof sheathing boards) did not have enough water available for biological growth; surfaces like OSB, plywood, vinyl siding, and painted wood siding, where the condensation sat for long periods of time, grew all manner of mold, mildew, moss, or fungi.

I think the mold in the attic of the Baker Brook home is the result of that stretch of weather, but I can’t prove that. On the other hand, that theory does not really change my recommendations for this homeowner regarding her attic: clean the mold with mild soap and water, let it dry, and air seal the attic.

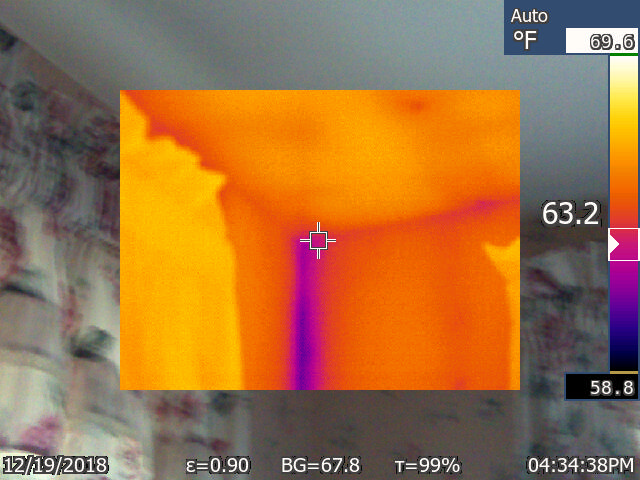

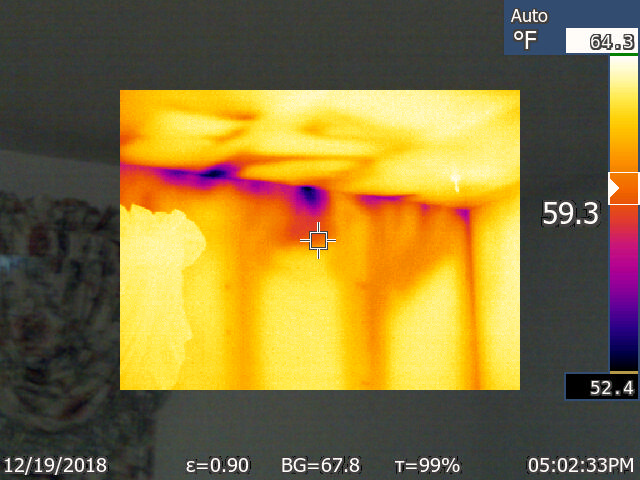

Infrared images are revealing

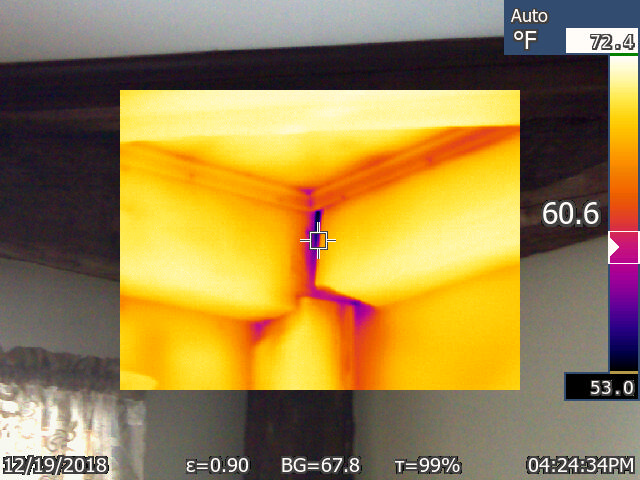

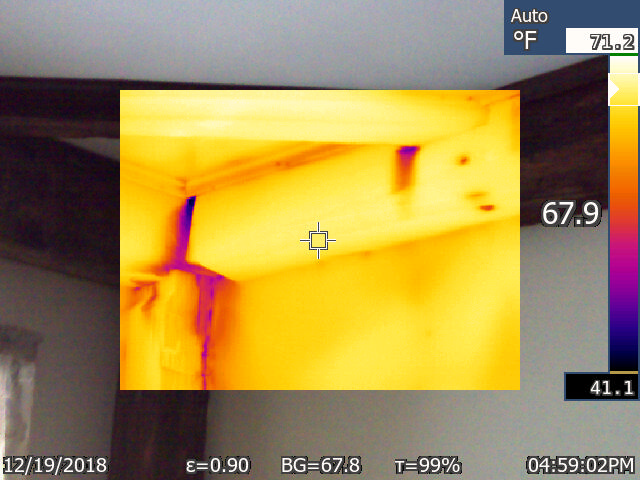

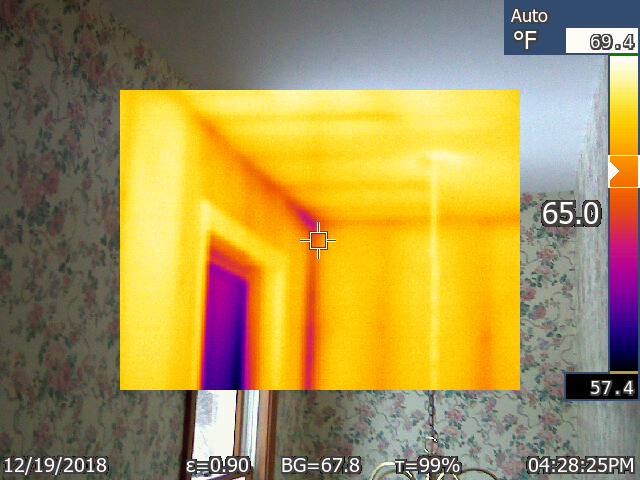

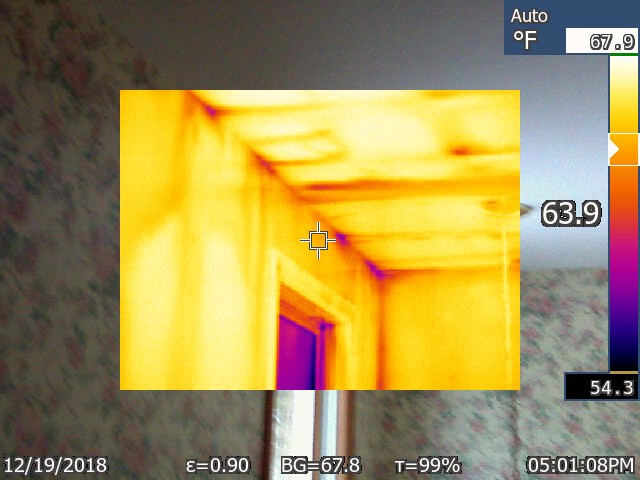

Take a look at the infrared images in the photo gallery. The IR images are in pairs, with one image taken with the blower door off, and the other taken with the blower door on (adjusted to -30 Pascals).

Image #7: Beams in the old living room; blower door is off.

Image #8: Beams in the old living room; blower door is on.

Image #9: Upstairs hallway; blower door is off.

Image #10: Upstairs hallway; blower door is on.

Image #11: The wall in the back bedroom on the second floor, near the eave; blower door is off.

Image #12: The same area shown in Image #11; blower door is on.

Whether or not the current attic mold is the result of environmental conditions or stack-effect driven air leakage does not change the need to air seal the attic.

I am now working with the insulation contractor on the issue of how “hygrothermal-ready” the attic is — or will be after the mold is cleaned up — for his work to proceed.